|

THE

RIVER LEA AND THE LEE NAVIGATION: TEN CENTURIES OF ENGINEERING AND

ENGINEERS

John H

Boyes,

Published in Papers of

the Rolt Fellows Edited

by R Angus Buchanan, Bath University Press, 1996

Introduction

Lea or Lee - which is correct? Both seem at times to be used

indiscriminately to describe the valley and particularly the river which

for centuries has formed the major part of the: boundary between

Hertfordshire and Middlesex on the west and Essex on the east. The river

itself rises further west still in the suburbs of Luton in Bedfordshire

and its eastward course from there to Ware follows the pre-first lee Age

valley of what was later to be known as the Thames. In that early period

the Thames flowed from Marlow in a north-easterly direction towards St

Albans and then easterly through Hertford, Ware and central Essex to the

North Sea. During the first Ice Age the terminal moraines of the great

glaciers dammed the course of the Thames so that a lake was formed in

the north of Essex. This eventually burst its banks and generated the

present Lea valley and the Thames estuary. Moraines from a later lee Age

created the present course of the Thames through London to link with the

earlier Thames estuary.1

In the post-glacial period early man settled in the Lea valley to take

advantage of the fresh water springs available for the necessities of

life and his successors in Saxon times called the river the Lygan or

Lygean,2 possibly the bright river. This was later corrupted

into various forms including Luy - hence Luton; Ley - hence Leyton; and

the Lea. But in 1739 when Parliament created a body of trustees to oversee the maintenance of the

navigation the Act referred to the Lee Navigation Trustees. Thus since

that time Lea is strictly the spelling for the valley and the original

river while Lee refers to the navigation and the artificial cuts made in

the valley to facilitate waterborne transport. Hence the distinction in

the spelling in the title of this essay.

Because of the fertility of the valley bottom, the

purity of the water, the value of the current in powering water mills,

and the beneficial direction of the river providing an easy

communication to the north of London the Lea valley became economically

important from very early times But in order to maximise these

advantages it has been necessary to improve radically the natural

conditions available. This process of improvement has been undertaken by

individuals and authorities for over a thousand years and the

consequence of some of the early activities still determines the work

that has to be done today.

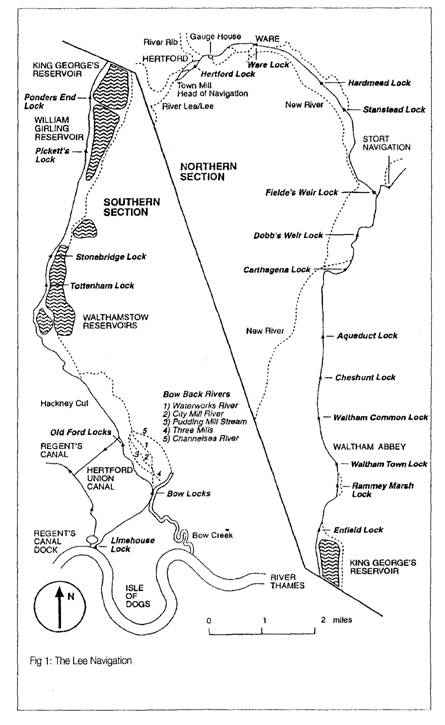

As already stated, the River Lea rises near Luton

at Leagrave Marsh - a place where the pure spring water attracted a

neolithic camp, possibly some 10 acres in extent 3. The river

then flows easterly through Luton Hoo Park, Wheathampstead, Hertford to

Ware. In its course it receives several tributaries, Mimram, Beane, Rib

and Ash, as well as a number of smaller streams. At Ware the river turns

south to pass Enfield, Walthamstow, Leyton and West Ham to enter the

Thames at Bow Creek. Between Ware and the Thames only one further major

tributary is received, the Stort, which also became a legal navigation

in 1769.4 In this basin over one hundred watermill sites have

been identified emphasising the economic importance of the water supply

as a source of energy.

The valley itself is fairly wide due to the lateral

movement over the centuries of the river bed and the regular flooding of

the valley bottom during the winter rains. This has enabled major

engineering works to be undertaken without undue difficulty but, on the

other hand, it has also limited the number of east-west crossings over

the marshland while permitting direct north-south communications.

As technical know-how increased and as

administration became more sophisticated so did the nature and scale of

improvements to and modification of the river gather scope and pace.

This is reflected in the three main periods in which different

approaches were made to solve the problems of the time.

The first period - by far the longest - covered the

years up to the mid-eighteenth century and was dominated by an ad hoc

approach to problems by the local landowners, great and small, and the

Commissioners of Sewers using local labour and almost parochial control

with inevitable disputes between interested parties. Sometimes recourse

was made to higher authority for arbitration and settlement of major

controversial matters and for sanction to carry out works but there was

no national guidance on methods to be adopted.

The second period between the mid-eighteenth

century and the second half of the nineteenth century coincided with the

rise and fall of national canal construction and well-known names from

the newly emergent civil engineering profession, such as Smeaton, Yeoman

and Rennie, were called in to advise as consultants. It was in this

period that most of the major alterations to the course of the

navigation were undertaken.

The third period dovetails into the end of the

second period by which time the professional engineering knowledge

previously found among a limited number of practitioners had spread to a

wide spectrum of trained men and the dominance of the few was no longer

necessary. It was during this period that the various authorities

recruited full-time trained staff who were assisted by specialist

consultants and contractors engaged on those occasions when major civil

engineering work outside the normal experience of the staff was

projected.

Although there is no clear-cut division between the

periods, the pattern of control can be seen to evolve gradually. In this

essay the three periods are dealt with separately but it must be

remembered that there is a continuum between them. The financial aspects

of the development and the growth of traffic on the navigation will not

be considered except incidentally.

|